Integrated Care Board structure

Integrated Care Boards report to NHS England, who answer to the Department of Health and Social Care, ran by the Secretary of State who is a member of the government’s cabinet.

The Health and Care Act 2022 sets out the structure of what an Integrated Care Board should look out. The board’s membership has to be a minimum of 10 people, featuring a chair, a chief executive, directors of finance, medicine and nursing, and two or more non-executive members – as well as three or more partner members (providers) from the local area. These partners are to be chosen via nominations from either the NHS trusts, primary care services, or local authorities within the ICB’s area. One of the above members is required to have knowledge of mental health services, or a specific member be brought in to represent them.

There are additional regulations restricting the appointment of a member if their involvement in private healthcare could impact or prejudice their duties on the board. Similarly, there are also caveats for permitting regular participants or observers to attend meetings – to encourage greater transparency.

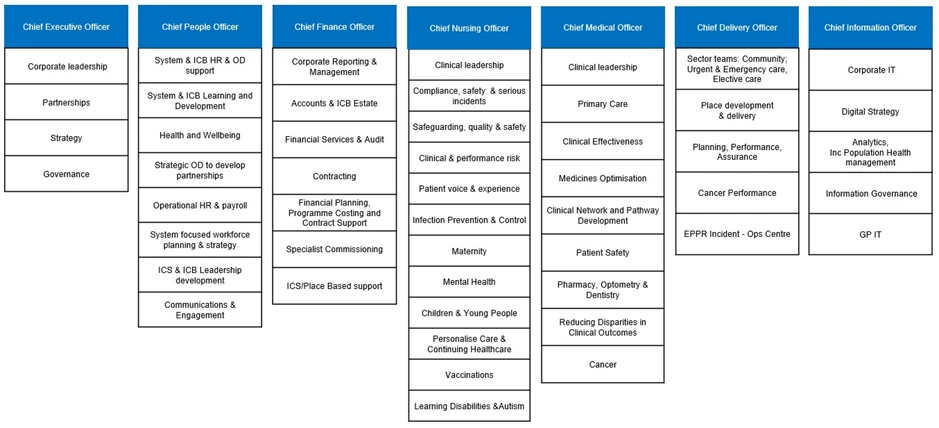

These graphics from the NHS Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West ICB detail the top of their ICB structure regards management, and who reports to whom.

NHS BOB helpfully give a more detailed breakdown that shows the responsibilities of each of these key positions, and what areas of the ICB fall under their control and management.

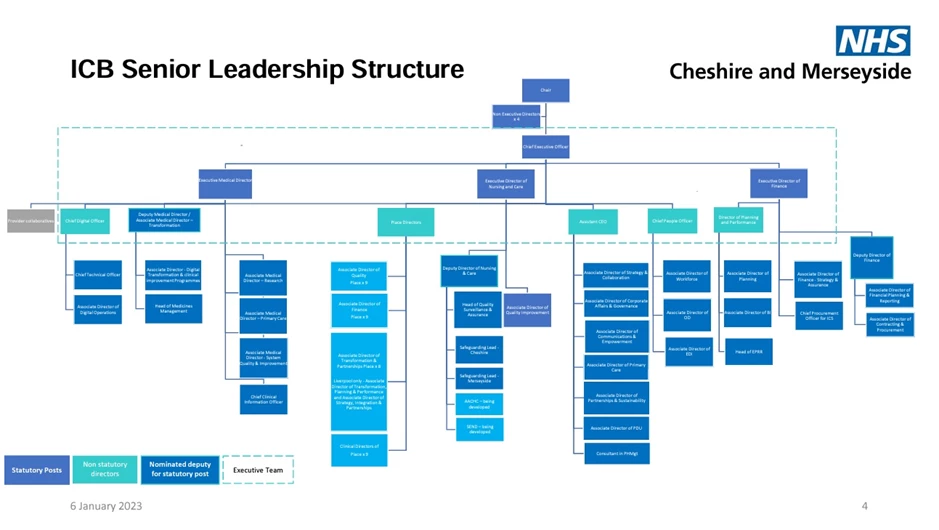

A more detailed structure can be found here from NHS Cheshire and Merseyside:

NHS England published an ICB model constitution template back in May 2022. This foundational document was to help set out the duties of integrated care boards, the reasoning behind NHS England pursuing integrated care services (ICSs), and instructions about how to set up in the new format. NHS Providers has a similar ICB governance document that offers a more concise explanation and rundown for healthcare professionals.

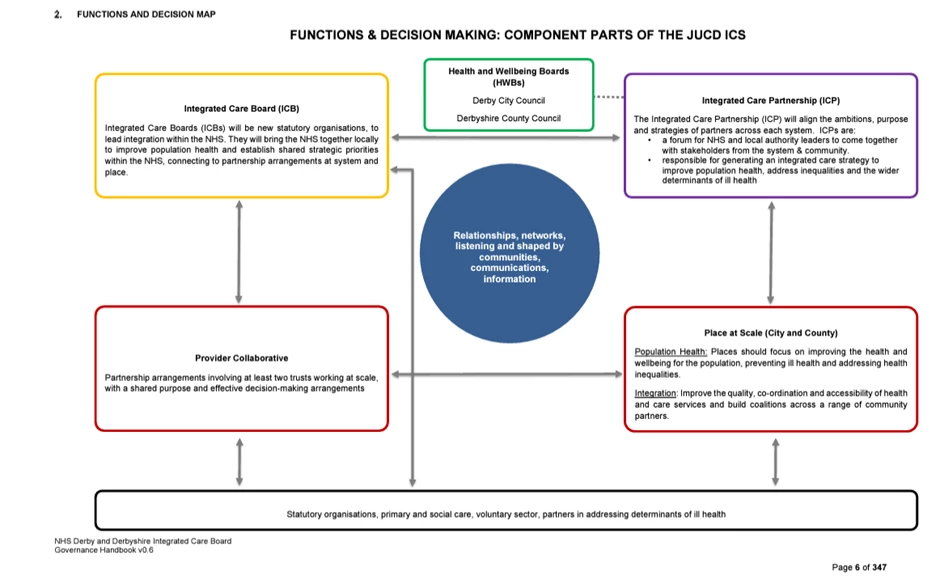

The bigger picture understanding of how an ICB fits into the larger English healthcare structure can be found from NHS Derby and Derbyshire ICB, which explains the interactions between different sections of the care network.

ICB restructure 2023

On March 2nd 2023, Health Service Journal reported that a 30% cut to ICB operational budgets was set to be implemented and required by NHS England. The breakdown of the cost-cutting was a 30% real terms reduction in expenditure within ICBs by 2025/26, but two-thirds of this reduction needed to be achieved by the end of 2024-25.

The main target of these cuts is staffing, which is a major part of ICB running costs. Redundancies were hinted at, with NHSE telling the press: “This provides time for ICBs to reorganise and gives some flexibility on funding change, with scope for ICBs to go further and faster where possible, enabling resources to be recycled into front line care.”

Days before this, ITV West Country reported that the NHS Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire ICB (BNSSG) was facing job cuts due to funding issues; shortfalls that the news report cites as being down to the end of the Covid pay award (support funding) and the then-rising inflation. Ironically, in the case of BNSSG, they actually reported a potentially reduced impact due to the volume of vacancies the ICB had and could thus avoid voluntary redundancies.

ICB running costs

The cost of running an ICB – within a wider Integrated Care System – is sizeable. Government funding is paying of staff, estates, medication, and training, but the necessity of the ICB restructuring is partly due to these costs being exorbitant.

The HSJ has an article on ICSs missing financial plans despite NHSE claims more would deliver. Their investigation found that, for 2023-24, a total of 25 integrated care systems out of the 42 overall had missed their financial targets. This is up from 18 the year previous – despite NHSE executives saying they think things will bounce back.

The response locally, according to the HSJ, is that these targets were unrealistic – especially when planning for a £650 million deficit that turned out to be more like £2 billion. The HSJ says that this deficit was so damaging that “Midway through the year, the Department of Health and Social Care and NHSE were forced to raid central budgets for tech and capital, alongside additional cash injections from the Treasury, to mitigate the costs of industrial action.”

This brings up an important point about lost productivity and higher staffing costs, and a big part of those staffing costs are the agency fees for temporary or short-term clinicians – something we’ll touch on shortly.

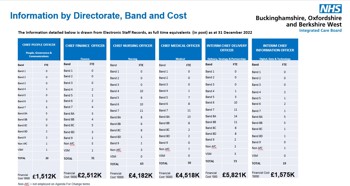

Before then, it’s important to assess what ICBs are spending on staffing ordinarily. The NHS Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West ICB website has documents available to the public regarding ICB structure. From their disclosures, they spend £1,372,000 in salaries on the seven members of the Executive leadership.

Below is a financial listing of staff per pay band under each executive’s management, and the overall running costs that each executive is responsible for.

Each branch costs the following:

- People, Governance and Comms: £1,512,000

- Finance: £2,512,000

- Nursing: £4,182,000

- Medical: £4,518,000

- Delivery, Strategy and Partnerships: £5,821,000

- Digital, Data and Technology: £1,575,000

This is a total of £20.12 million, plus the executive pay of £1,372,000 means a total of £21,492,000. Broken down, this means NHS BOB needs to save £6,447,600 by the end of 2025/26; £4,298,400 which needs to be achieved by the end of 2024/25 and the remaining 10% or £2,149,200 a year later. This would bring the ICB staff spending down to £15,044,400.

The three biggest sections above are delivery, medical, and nursing – but it is nursing that is most in need of adjustments and improvement. A large contributor to such high costs is the use of agency staff. The NHS does have a staff bank to utilise clinicians from other departments and even other neighbouring trusts, but issues with the speed of pay for performing overtime are considered a hindrance towards encouraging staff to take on the overtime.

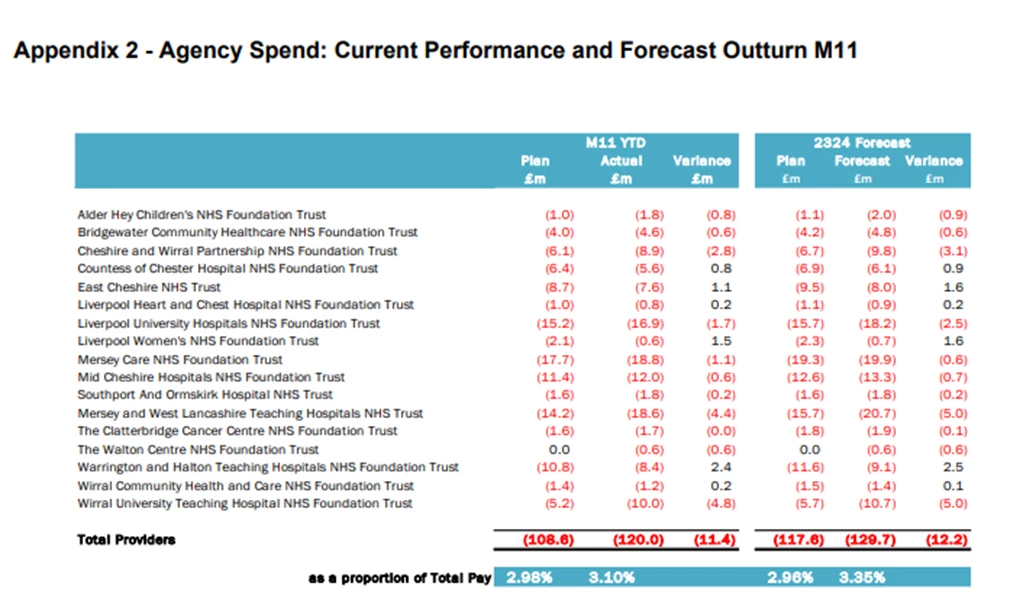

The alternative, and a necessity in these cases, is the use of agency staff. This is a more expensive choice however, as detailed in the NHS Cheshire and Merseyside spending table below, sourced from their 2022/23 annual report.

Beyond this, there’s also the matter of estates. The land and property used by the NHS has a cost, as do the salaries for those staff members required to operate or maintain the facilities. Digitisation helps avoid some of this burden, by removing the need to store large wads of paper documents for patients and operations, but there are still some issues that can’t be avoided.

NHS Cheshire and Merseyside, in the same annual report linked above, highlights the problem of rising energy prices – a jump from £41 million to £110 million at current rates. There’s also the challenge of decarbonisation aka green policies. Environmentally conscious actions like LED lighting over standard bulbs is simple and sensible, a relatively quick return or benefit to investment. Other aspects of change need more of a capital investment though, and that takes a lump sum out of a tight budget at what could be argued as the worst time financially for the NHS.

NHS workforce management

This brings us onto workforce management within the NHS – perhaps the most easily addressed aspect of ICB structure and financing.

Better utilisation and application of the workforce can help reduce the need for agency staff. Industrial action can’t be helped from the NHS’ point of view (that’s a government problem) but better recruitment and better staff retention will alleviate problems.

Digitisation is a part of the NHS Long Term Plan, and something that very much involves us here at The Access Group as a solutions provider. Digital maturity through integrated software and the benefits of joined-up care within hospital or trust settings will help relieve the work burden on clinicians, thus reducing staff turnover due to burnout or frustration at working conditions, but it’s not enough to really impact the shortage of overtime interest in filling the staffing gaps.

We’ve previously talked about Access PayWise+ and how we’re utilising this software to help the NHS by offering prompt payments for staff so that they can benefit from working the overtime – rather than having to wait for a delayed payment from their trust. Nursing Times has published several articles on nurses using food banks, and while wages are varied depending on banding, there are plenty in the NHS on lower end salaries who would perhaps pad their income with overtime were they able to take receipt of the funds quickly.

It's not just the wages and overtime though. HSJ again reported on an important issue of software choice and how North Devon got an all-in-one solution package three years ago but isn’t making the most of it – describing it as a Rolls Royce EPR being driven like a Ford Focus.

Again, at Access we’ve discussed all-in-one versus best of breed. Choosing the right software is important given the lump sum expense involved, and it’s the same problem as the decarbonisation being felt in the NHS estates sector. Big projects to achieve big goals need a large sum of money to get the ball rolling. Done properly they will, in time, make returns and be a worthy investment, but a mistake due to a lack of due diligence or foresight regarding utility can be very costly – quite literally.

Our argument, and our approach, is to modernise existing systems by integrating our solutions and making things interoperable. This spares an ICS from having to do a mass overhaul at cost, and instead just embellishes what’s already there – with new modern technology allowing the expansion and further, more complex development.

The final point comes from The Municipal Journal (the MJ). They recently published an article about fears over ICB cuts impact. At present, one aspect of NHS optimisation has been greater community and VCSE collaboration; taking the care to the grassroots as it were so that prevention can have an impact rather than reactive care. Better habits and planning can beat taking action after the fact, and is a cheaper way of supporting health and wellbeing. The problem is that ICB allocations for funding are heavily in favour of acute care rather than anything else, and now the King’s Fund – as cited in this MJ article – fear the local or community partners will be the ones to suffer due to the cuts and deficits.

This is a major problem for ICBs, because they can’t just palm things off onto local councils, so there needs to be the restructuring to ensure that funding and capacity are there to continue to build on these connections and relationships and to build this bigger network of joined-up care.

The future is digital, and with software the NHS can spare itself the disaster of collapse or the ignominy of falling out of favour slowly over time. The important thing though is that change MUST happen – ICBs cannot continue running at a deficit and maintaining services and quality. Something will give, and in both cases people get hurt. It’s time for change.

AU & NZ

AU & NZ

SG

SG

MY

MY

US

US

IE

IE